Nicaea, The First Ecumenical Council, Christianity, and Emperor Constantine

Updated May 2, 2016

Summary

I became fascinated with finding the site of the first council of Nicaea which was held in Emperor Constantine’s summer palace in Nicaea, Turkey (now called Iznik), in 325 AD. That first ecumenical council of the Catholic Church was very important for many reasons. While the Iznik area has many historical and archeological sites, and in spite of extensive searching, we could never find a single, unique and compelling place to look or dig. But the search was amazing and enriching. Here is a short summary of our efforts.

Introduction

Scientists sometimes have the opportunity to give lectures and attend meetings all over the world, often in interesting places. Occasionally, these visits blossom into personal explorations of various kinds. This is a brief story of one of my explorations.

It started with a trip to a meeting in Istanbul, Turkey. On a day off, one of my Turkish colleagues recommended that I take a side trip to a village known as Iznik. Iznik is the modern name; it was known as Nicaea in ancient times. Nicaea was the site of the first ecumenical council of the Catholic Church in 325 AD. The name is still found the in the popular Nicene Creed. The council was held in the summer palace of Emperor Constantine (from Constantinople, now Istanbul) and was important for the formation, beliefs and practices of early and modern day Christians. It set the date for Easter and had implications for the fusion of Roman religion and state.

Its accomplishments included the construction of the first part of the Creed of Nicaea (again, commonly known as the Nicene creed today), pronouncements on the questions of the nature of the Son of God and his relationship to God the Father, and a promulgation of some aspects of early canon law. It wasn’t all fully accepted, but the council was a major event with major effects.

I more or less knew at the time that the council declared that Jesus Christ was divine (God), and that he was begotten, not made, meaning that he was the true Son of God. Also it was decided that he was of the same substance (homousios) as the Father.

Wow, I thought. All that happened in one place. Having been a Catholic in my childhood, I knew that these pronouncements shaped the church and its beliefs for thousands of years, and I soon decided that I wanted to find the place where all of that happened. I thought that visiting the summer palace where the meeting was held would be amazing. That began a several year exploration that unfortunately did not end in a full success, but the journey was fascinating, inspiring, and amazingly enriching.

First Start and First Visit

At the end of May, 1996, I attended a Neuroscience meeting in Istanbul, I think in the Kalyon Hotel. On our afternoon off from science, on the recommendation of my Turkish friend, Sakire Pogun, I went to Iznik which was several hours by car. When we arrived, we had a tour of the Iznik area and I found out that the site of Constantine’s palace was unknown as indicated by the driver’s shrug and blank look when I asked about it. But my interests were stirred.

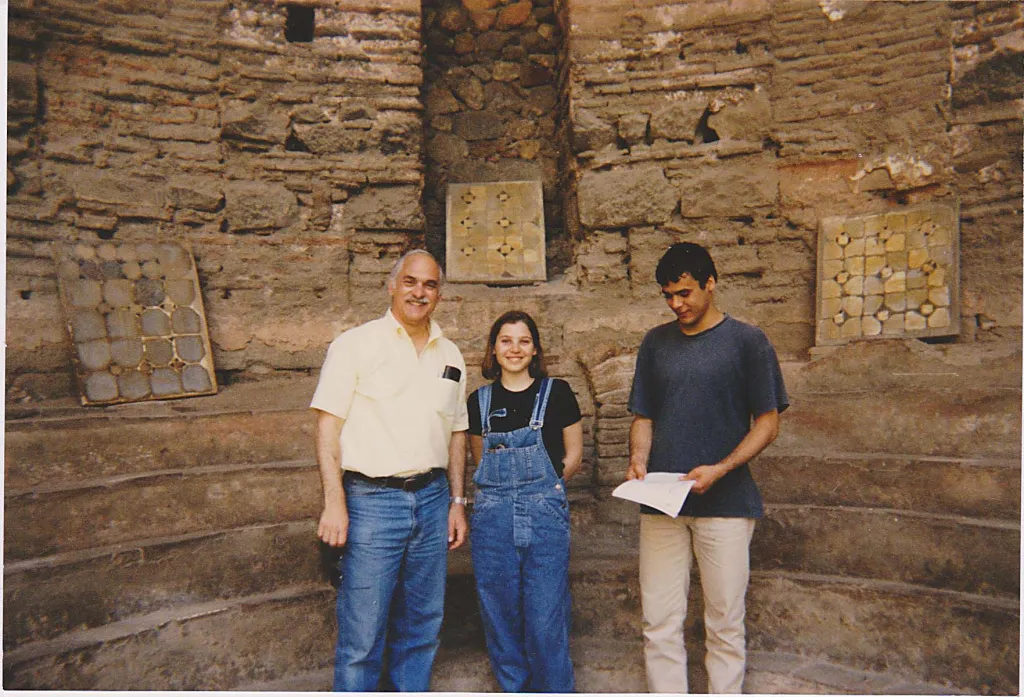

This was I think my first trip to Iznik with Yuksel Pogun (center), the daughter of a colleague, and a friend (right). They were my guides and thankfully, translators. The site shown is the Hagia Sophia, the site of the second council of Nicaea which occurred in 787AD. So there were two councils, and this article is mainly about the first council. But we did visit the shown church where the second council was held. That site is not lost, although it is in ruins. Picture taken in 1996.

This was one of my first views of the Iznik area. It was very surprising and a great memory. The man in front is actually a goat herder watching his goats who are out of view. In the background, you can make out the stone steps laid out in an arc which is the remains of the Roman Theater in Iznik! It seems to be somewhat neglected, probably because there are so many of these kinds of ruins in Turkey. Every time I visited Iznik, I always returned to the old Roman Theater with the grazing animals to remind myself how ancient the city really was. The Photo was taken probably in 1998 or so.

Beginning the Search

Through other friends in Turkey, I got to meet Prof Semavi Eyice, who was generally knowledgeable about the history of the Iznik area. He was a professor of Byzantine art history. We found out that the location of the palace was unknown and possibly near the lake, since Constantine travels there by boat.

In late June of 1998, I found myself in Berlin at another meeting, and because of the major role of German archeologists in Turkey, I enquired about Iznik/Nicaea. One of my best friends, Dr Hans Rommelspacher, helped me find the knowledgeable people. At the Free University of Berlin, I met with Prof Hans Nissan who recommended a number of books and articles (unfortunately, many of them in Turkish or German). I also got an introduction to Prof Dr H Hauptmann at the German archaeological Institute in Istanbul. Hauptmann was one of the most welcoming and helpful people I met in this quest. He told me about a process called geomagnetic mapping that would identify Roman walls. I also met with Prof Heilmeyer who was the Director of the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. These German scholars, internationally known in their fields, were very helpful. Basically, I found out again that the site of the Palace was not known. But they offered to help if they could. They suggested I contact Bedri Yalman the Director of the Iznik Museum. Dr Ersin Koylu, a personal friend at Ege University, was helpful in reaching the Turkish archeologists and setting up meetings. Importantly, he translated everything.

In the meantime, my friends in Turkey were amazingly helpful. They got documents, maps, commentaries and other material that would have taken me years to get by myself.

Some Hints

By September of 1998, we were beginning to get an idea of possible sites of the Palace. There was an area in Iznik called the “Garden of the Palace.” The inhabitants of the city suggested that the Palace was outside the walls of the city. But no one was sure. There were at least two lost palaces, Constantine’s which we were searching for, one associated with Theodoros Laskaris (Emperor of Nicaea in the early 1200s.), and there was possibly a lost Ottoman palace as well. In addition, there were many lost temples of note. So, it looked like there were many lost buildings from that era, which complicated the search for any specific one.

I also discovered that there as a war in that area with the Arabs in about 900 AD, and during the war, old buildings and ruins were stripped and moved to form a wall around the city. When there, I saw the arm of a granite statue protruding from a busted part of the impressive wall. So what would be left of the Palace? Local traditions and stories were likely to be unreliable. It was frustrating that there was no physical evidence that the Palace was there, in spite of abundant and reliable ancient and more recent records and documents.

We decided to think about it more and to get an idea of what the Palace might look like. Accordingly, I read about typical Roman palaces of that era and got an impression about their construction, size and layout. I found out about tripartite reception halls, triumphal arches, areas for ladies, and inner rooms. I contacted (or tried) other scientists who had worked in Turkey and Iznik, and found that many of them were old and perhaps dead. I found the people who could do geomagnetic mapping. I learned more and more.

What the Palace Most Likely Looked Like

We considered the council itself and what the attendees said in their writings. Many of them wrote to their parishioners about the council. Socrates Scholasticus, a fifth century historian was in touch with the relevant tradition and sources, described much about the council. Pamphilus (wrote about the life of Constantine) and other writers described the dinners, the guards, the numbers of seats, and the arrangement of such events. Sources say the bishops numbered more than 250 and their attendants were large in number, totaling perhaps about 2000. Such a large number placed requirements on the meeting areas. When I presented this information to Bedri Yalman, he was seemingly impressed and even excited. The Palace was not a small structure. But I guess we knew that but it didn’t help us find the location of the Palace.

After Years of Searching

After a long and thorough search, we could not find a likely location of the palace. If we searched further, we might have found some old Roman sites, but the historical presence of many old Roman and more recent structures would make identification difficult. Surprisingly, there was no physical evidence that Constantine visited there, although we know he did because of abundant historical writings.

I thought of going door to door to ask the citizens if they knew of ruins, perhaps even in their basement. But the Turks felt that was not going to be helpful. Also, being an American did not help either. The Catholic Church, who would have a strong interest in the site, had not been active there most likely because it was in a Muslim country. Hauptmann, at the German Archeological Institute in Istanbul, cautioned me about getting in over our heads without solid leads. Also, a practical matter was that many of us were running out of vacation time.

So we decided to suspend the search, and hoped that some leads would develop in future years. I still inquire when I can. For example, after an earthquake in the area, which I dreamt might expose some places of interest, I called my friends in Turkey. But they had no useful new information. So, now, we go on with our lives and wait and hope that a good clue develops.

The man in the foreground is Bedri Yalman, the archeologist in charge of the Iznik area. He was very helpful. The person behind him is Ersin Koylu, a dear friend and scientific colleague. Bedri is shown explaining the art of wall construction by the Romans. The exact date of the picture is not certain, but it is around 2000.

The Palace Team

The group of us interested in finding Constantine’s summer Palace, the site of the first ecumenical council, was referred to as the “palace team.” The main members were me, Sakire Pogun, Ersin Koylu and Hans Rommelspacher.

Sources

The sources that were consulted included many interviews and discussions with experts as described above, and historical texts (unfortunately mostly in Turkish). An especially useful text about the “History of the First Council of Nicaea” is in the Pitts Theological library at Emory (BR210.D8, 1886).